-40%

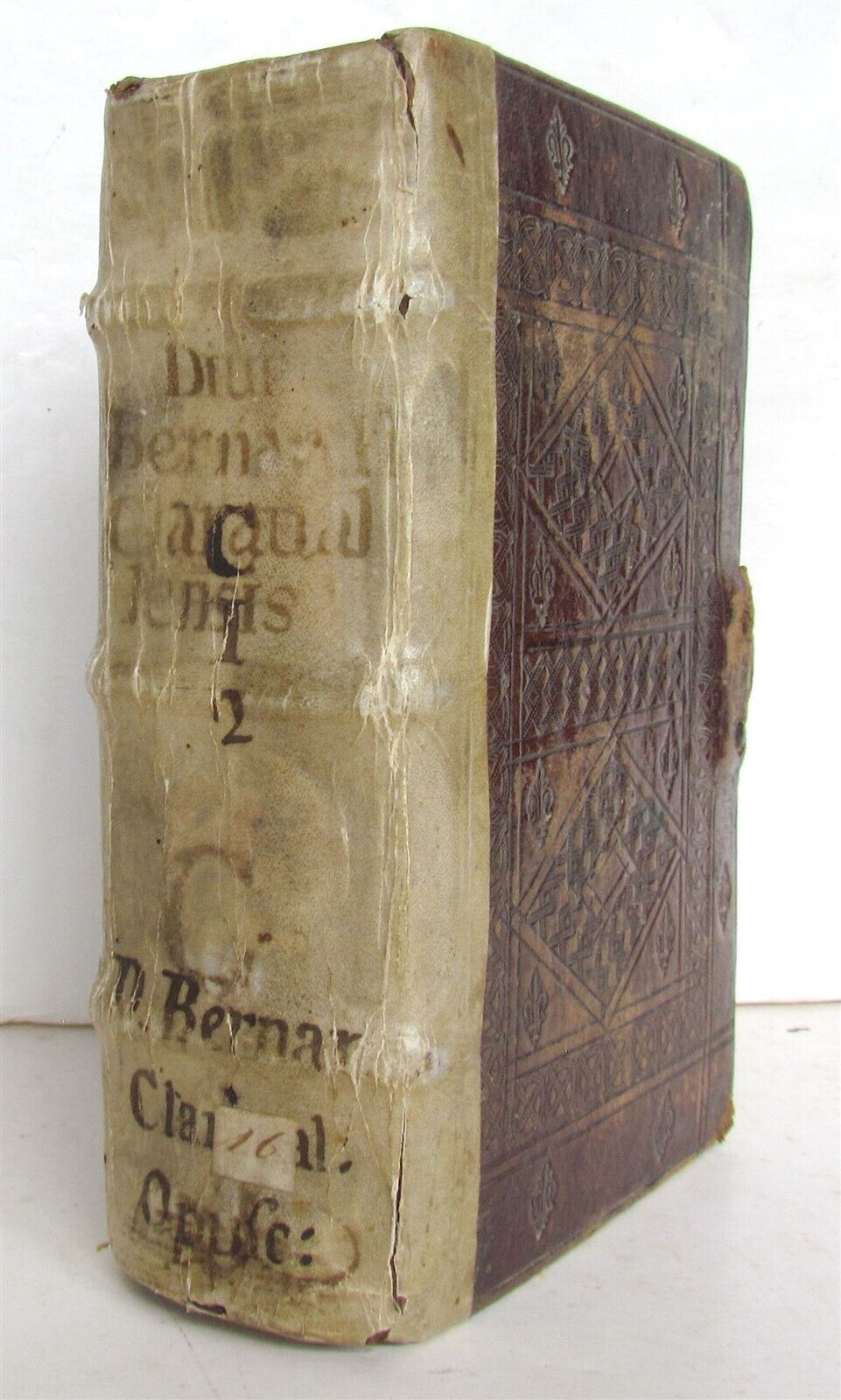

Page 203 of Incunable Nuremberg chronicles , done in 1493 (old German)

$ 87.11

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

This is the page 165 from the famous book the chronichles of nueremberg , so far so on the history of the world as they sawuntil 1493

It was a very famous book, and still today their sheets are sold in big auction houses. This is particular is in German. Only 300 exemplars are know to survived nowadays.

you can check more information here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuremberg_Chronicle

FOLIO CCIII recto

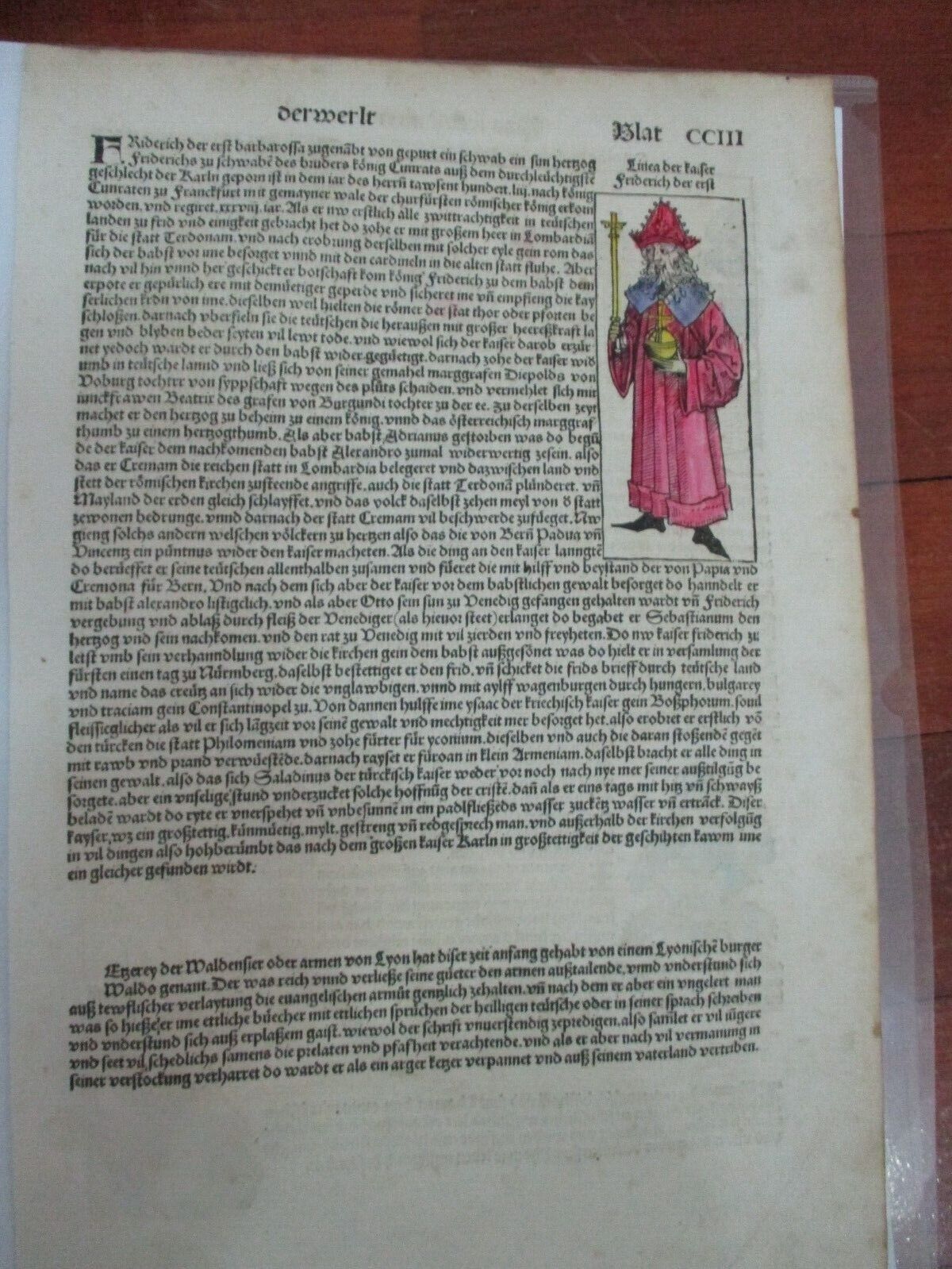

Frederick (Fridericus) the First, surnamed Barbarossa, a native of Swabia, son of Duke Frederick of Swabia (a brother of King Conrad), was born of the illustrious line of Charles the Great. He was elected to succeed King Conrad at Frankfurt, in the Year of the Lord 1153, at a general election held by the electors; and he reigned 33[The Latin edition of the concerning the reign of Frederick Barbarossa is incorrect. The German edition corrects the mistake and prints 38 years.] years. After he settled all controversies and restored peace in Germany, he proceeded to Lombardy with a large army, appearing before the city of Tortona (Terdonam)[Tortona (ancient Dertona) is a town and Episcopal see of Piedmont, Italy, and on the main line from Milan to Genoa. Dertona is spoken of by Strabo as one of the most important towns of Liguria, and the local museum contains Roman antiquities found there. In the Middle Ages Tortona was zealously attached to the Guelphs, on which account it was twice laid waste by Frederick Barbarossa in 1155 and 1163. In 1176 it made a treaty with Barbarossa and the people of Pavia, and was taken back into favor by Henry VI in 1193.]. Having taken that city he proceeded to Rome with such speed that the pope with his cardinals fled in fear to the Old City[This probably refers to Leonine city, the so called

Civitas Leonina

, a part of Rome built by Leo IV (847-855) on the right bank of the Tiber. It now includes the Borgo, the castle of St. Angelo, St. Peter’s and the Vatican.]. But after the exchange of many messages King Frederick came to the pope with due respect and humility, assured the pope of safety, and received of him the imperial crown. At the same time the Romans kept the gates of the city of Rome closed, and afterwards with a large force fell upon the Germans who remained outside. Many were slain on both sides. This enraged the emperor, but the pope pacified him, and the emperor returned to Germany. On the ground of consanguinity he divorced his wife, the daughter of Margrave Diepold of Voburg, and espoused Beatrice, daughter of the count of Burgundy. Simultaneously he made the duke of Bohemia a king, and made a duchy of the Austrian margraviate. But after Pope Adrian’s death the emperor became antagonistic to Alexander, his successor; and he besieged the wealthy city of Crema[Crema, a town and Episcopal se of Lombardy, in the Italian province of Cremona, and 26 miles northeast of the town of Cremona. In the 12th century Cremona attacked it and Milan sided with it. Barbarossa sacked it in 1160, but it was rebuilt in 1186. It fell under the Visconti in 1338, joined the Lombard republic in 1447, and was taken by Venice in 1449.], in Lombardy, and attacked the estates and territories of the Roman Church at the same time. He also plundered the city of Tortona, leveled Milan to the ground, and forced the inhabitants to take up their abode at a distance of ten miles. He also caused the city of Tortona much distress. These proceedings so touched the hearts of the rest of the Italian people that those of Verona, Padua, and Vicenza formed an alliance against the emperor. When news of this reached the emperor, he called together all of his Germans, and with the assistance of those of Pavia and Cremona, proceeded to Verona. But since the emperor feared the power of the pope, he craftily negotiated with the pope. When the emperor’s son Otto was taken prisoner at Venice, and Frederick secured pardon and absolution through the diligence of the Venetians, as stated above, he made gifts to Duke Sebastian and his successors, and endowed the senate of Venice with privileges and treasures. Now when Emperor Frederick was at last reconciled to the pope in the matter of his dealings against the church, he held a session of the princes at Nuremberg; and there he confirmed the peace treaty and published it throughout Germany. Then he took up the Cross against the infidels, and with eleven wagon-forts proceeded through Hungary, Bulgaria, and Thrace to Constantinople. From there he was assisted to the Bosphorus by Isaac, the Greek emperor. He took the city of Philomenia from the Turks, and then appeared before Iconium, plundering and burning it and the adjacent country. He then proceeded to Lesser Armenia, where he subjugated everything, so much so that Saladin, the Turkish sultan, was never before nor at any time since more worried about his extinction. But an unhallowed hour undermined the hopes of the Christians; for one day when the emperor was heated and covered with sweat he accidentally or thoughtlessly went into a stream of water to bathe; and he was drowned. This emperor was a magnanimous, shrewd, mild, strong and righteous man; and, except for his persecutions of the church, so highly esteemed, that in greatness of accomplishment the like of him is hardly to be found in history after Charles the Great.

Frederick I (c. 1123-1190), Holy Roman emperor called “Barbarossa” or “Red Beard” by the Italians, was the son of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, duke of Swabia, and Judith, daughter of the Welf Henry IX, duke of Bavaria. When his father died in 1147, Frederick became duke of Swabia, and immediately afterward accompanied his uncle, the German king Conrad III, on his disastrous crusade. In 1152 the dying king advised the princes to choose Frederick as his successor to the exclusion of his own young son. Frederick was chosen German king at Frankfort in 152, and crowned at Aix-la-Chapelle. He owed his election party to his personal qualities, and partly to the fact that the united in himself the blood of the rival families of Welf and Waiblingen.

Frederick’s first concern was to establish peace at home. For this purpose he issued a general order, and was prodigal in his concessions to the nobles. He divorced his wife Adelheid on the ground of consanguinity. In 1153, he concluded a treaty with the pope by which Frederick, in return for his coronation, promised to make no peace with Roger I, king of Sicily, or with the rebellious Romans, without the consent of Eugenius, and generally to help and defend the papacy. In 1154, he made the first of six expeditions into Italy, during which the subjugation of the peninsula was the central aim of his policy. He was crowned emperor at Rome in 1155. But disorders were again rampant in Germany, especially in Bavaria. Frederick restored peace by vigorous measures; Bavaria was transferred from Henry II Jasomirgott, margrave of Austria, to Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony; and the former was pacified by the erection of his margraviate into a duchy, while Frederick’s stepbrother Conrad was invested with the Palatinate of the Rhine. In 1156, the king married Beatrix, daughter and heiress of the dead count of Upper Burgundy. An expedition into Poland reduced Duke Boleslaus IV to submission, after which Frederick received the homage of the Burgundian nobles.

In 1158, Frederick sent out his second Italian expedition, during which imperial officers called ‘podestas’ in the cities of northern Italy, captured Milan (which had revolted), and the long struggle began with Pope Alexander III, who excommunicated the emperor in 1160. During this visit, Frederick summoned the doctors of Bologna to Roncaglia in 1158, and, as a result of their inquiries into the rights belonging to the kingdom of Italy, he obtained a large amount of wealth. In 1163, his plans for the conquest of Sicily were checked by a powerful league against him, provoked by the exactions of the podestas and the enforcement of the rights declared by the doctors of Bologna. Frederick had supported an antipope, Victor IV, against Alexander, and, on Victor’s death, a new antipope, Paschal III, was chosen to succeed him.

In 1166, he made his fourth journey to Italy. Having captured Ancona, he marched to Rome, stormed the Leonine city, and procured the enthronement of Paschal, and the coronation of his wife Beatrix; but the sudden outbreak of a pestilence destroyed the German army and drove the emperor to Germany. During the next six years, the imperial authority was asserted over Bohemia, Poland, and Hungary. Friendly relations were entered into with the emperor Manuel, and a better understanding was sought with Henry II, king of England, and Louis VII, king of France.

In 1174, Frederick made his fifth expedition to Italy. The campaign was a complete failure. The refusal of Henry the Lion to bring help into Italy resulted in the defeat of the emperor at Legnano in 1176, when he was wounded and believed to be dead. He concluded with Alexander the treaty of Venice (1177), and at the same time a truce with the Lombard league was arranged for six years. Set free from the papal ban, he recognized Alexander, and, in 1177, knelt before him and kissed his feet. Henry the Lion was deprived of his duchy, and sent into exile. Frederick’s son was betrothed to the daughter of Roger I of Sicily. The question of Matilda’s estates was left undecided, and Pope Lucius III, whom Frederick met at Verona to establish friendly relations, was reticent because the betrothal of Frederick’s son Henry to the daughter of Roger I of Sicily threatened to unite Sicily with the empire. Lucius refused to crown Henry or to recognize the German clergy who had been ordained during the schism. Frederick then formed an alliance with Milan, where the emperor, who had been crowned king of Burgundy, or Arles, at Arles in 1178, had this ceremony repeated in 1186; while his son was crowned king of Italy, and married to Constance, daughter of Roger I, king of Sicily, who was crowned queen of Germany.

The quarrel with the papacy was continued with the new pope Urban III, and open warfare was begun. But Frederick was recalled to Germany by the news of a revolt raised by Philip of Heinsberg, archbishop of Cologne, and instigated by the pope. Hostilities were checked by the death of Urban and the election of a new pope as Gregory VIII. In 1188, Philip submitted, and immediately afterward Frederick joined the Third Crusade with a splendid army. Having overcome the hostility of the Eastern Roman emperor Isaac Angelus, he marched into Asia Minor. On June 10th, 1190, Frederick was either bathing or crossing the river Calcycadnus (Geuksu) near Seleucia (Selefke) in Cilicia, when he was drowned. The place of his burial is unknown, and the legend which says that he still is in a cavern in the Kyffhaeuser mountain in Thüringia waiting till the need of his country shall call him, is now thought to refer at least in its earlier form, to his grandson, the emperor Frederick II. He left by his wife Beatrix five sons, of whom the eldest became emperor as Henry VI.

The Heresy of the Waldensians or Poor of Lyons, had its inception at this time through one Waldo (Vualdo), a citizen of Lyons. He was rich and caused his estate to be distributed to the poor. Through diabolical instigation he undertook to observe in its entirety the poverty of the evangelists. But as he was an uneducated man, he caused some books to be written for himself, containing sayings of the German saints, or to be translated into his language; and prompted by an inflated spirit, he dared to preach, although he did not understand the text. He collected many disciples and sowed much injurious seed, ignoring the prelates and the clergy. When after many warnings he persisted in his ignorance, he was excommunicated as a heretic, and driven from the country.[Waldensian is a name given to the members of a Christian sect which arose in the south of France about 1170 as a protest against the system of a rich, powerful, and worldly church, with Rome for its capital, which had its inception when Pope Sylvester gained the first temporal possession for the papacy. Against this secularized church a body of witnesses silently protested; they were always persecuted, but always survived, till in the 13th century a desperate attempt was made by Innocent III to root them out from their stronghold in southern France. It was in the year 1170 that a rich merchant of Lyons, Peter Waldo, sold his goods and gave the proceeds to the poor; then he went forth as a preacher of voluntary poverty. His followers, the Waldensian, or poor men of Lyons, were moved by a religious feeling which could find no satisfaction within the actual system of the church as they saw it before them. Waldo had a translation of the made into Provencal, and his preachers explained the Scriptures. Pope Alexander III, who had approved of the poverty of the Waldensians, prohibited them from preaching without the permission of the bishops (1179). Waldo answered that he must obey God rather than man, and was excommunicated by Lucius III in 1184, and his followers persecuted from place to place. In 1487, Innocent VIII issued a bull for the extermination of the Waldensians, who had taken refuge in the retired valleys of the Alps. Little settlements of heretics dispersed throughout Italy and Provence looked to the valleys as a place of refuge, tacitly regarding them as the center of their faith. Under the bull of the pope they were attacked in Dauphine and Piedmont at the same time, and were sorely reduced by the onslaught. They finally became absorbed in the general movement of Protestantism. The Waldensians, the Wycliffites, and the Lutherans were very similar in their reforms.]

FOLIO CCIII verso

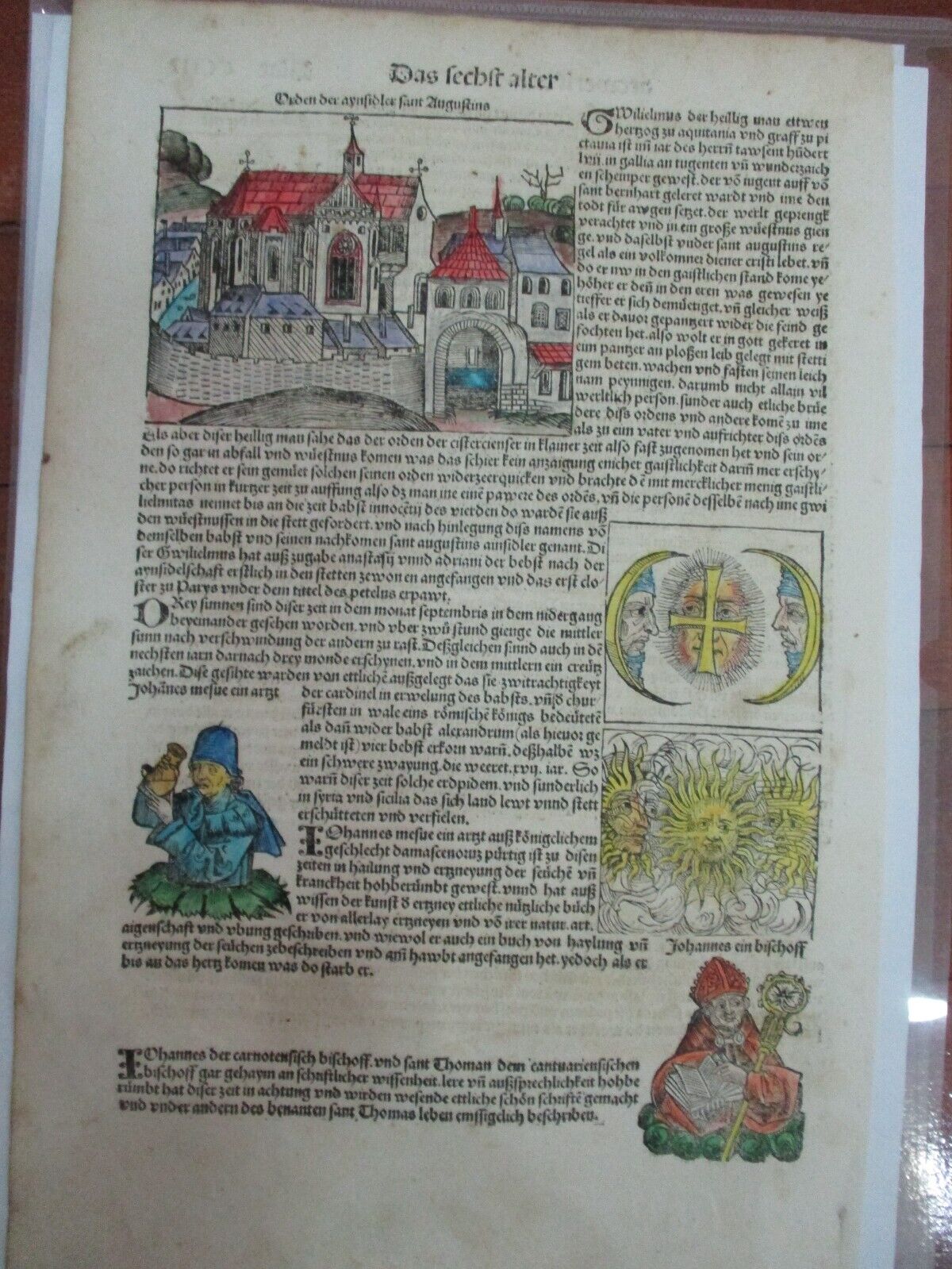

William (Guilielmus) the holy man, once Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitiers, was illustrious in the Year of the Lord 1157, in Gaul, for his virtue and miracles. From youth he had been taught by the Blessed Bernard. Realizing the presence of death, and scorning the pomp of the world, he went into a vast wilderness; and there he lived as a full-fledged servant of Christ, under the rule of Saint Augustine. Having entered upon a spiritual life, he now lived in the depths of humility, as once upon a time he had lived in the heights of honor. And as he had fought against the enemy, clad in armor, so now, in penance, he confined his naked body in the armor of God by constant prayer, watching, and fasting. For this reason not only laymen, but also a number of brothers of this and other orders, came to him as to a father and as the founder of this order. But when this holy man saw that the Cistercian order had increased much in a short time, while his own had declined and become so barren that it gave but little evidence of sanctity, he turned his mind to the resuscitation of his own order. By a remarkable increase in its spiritual membership, he brought the order into such ascendancy that he became known as its founder, and the monks were called Williamites (Guilielmite) up to the time of Pope Innocent the Fourth, when it was transferred from the wilderness to the city and its name changed by the same pope and his successors to the Hermits of Saint Augustine. This William, with the consent of popes Anastasius and Adrian, began to live in the city; and he built the first monastery in Paris, under the title of the Mendicants.[In the time of Innocent IV, all the hermits solitaries and small separate confraternities, who had lived under no recognized discipline, were registered and incorporated by a decree of the Church, and reduced under one rule, called the rule of St. Augustine, with some more strict clauses introduced, fitting the new ideas of a monastic life. Innocent IV died before he had completed his reform, but Alexander IV carried out his purpose. At length these scattered members were brought into submission, and the whole united into one great religious body (1284) under the name of Eremiti or Ermitani Agostini, hermits or friars of St. Augustine; in English, Austin-Friars. Nothing is known of the birth of William, the founder of this order, nor of his early life, on which he preserved an impenetrable secrecy. Several writers have confused this William of Maleval with William of Mariemont, and even with William I, Duke of Aquitaine, and William IX, Duke of Guienne. It seems that in the year 1153 there appeared in Tuscany a man who sought to conceal himself from his fellow men. The islet of Lupocavio, in the district of Pisa, seemed to answer his desire. There he constructed a small habitation, and his edifying example attracted a number of persons to him. They undertook to follow his rule of life, and their undisciplined manners obliged him to withdraw from his solitude to Monte Prunio, where he erected a hut in order to be alone with his God. But he was soon joined by idle vagrants, under pretense of a religious life. Their hypocrisy drove him again from his resting place, or the miscreants ejected him because they could not bear his sanctity. William returned to the island of Lupocavio, but not finding his former associates, he fixed his habitation in a desert valley, called at that time the “stable of Rhodes,” but since known as “the bad valley” (Maleval). It was situated in the territory of Sienna, about a league from Castigline, Pascara, and Buriano. It was in 1155 that he hid himself in this solitude, but in the beginning of 1156, he received a discipline, named Albert, who wrote the account of the close of his life. William practiced surprising austerities; thrice in the week he took only very little bread, and wine much diluted; on the other days he took bread, and herbs, and water. He wore sackcloth next his skin, and slept on the bare ground. He was endowed with a gift of prophecy. He died in the arms of Albert after having received the last sacraments from a priest of Castigline, who had been warned of the illness of the hermit. William was buried in his little garden. After his death, his disciples preserved the spirit of penitence and mortification with which he had inspired them during his life, and they endeavored to follow his maxims as their rule. And thus originated the order of Williamites (Guillemites), which rapidly spread from Italy, through France, the Low Countries, and Germany. From 1256, they had a monastery at Montrouge, near Paris, and were called White Mantles (Blancs-Manteux) from the great white mantles which they wore. They ceased to exist long before the French Revolution.]

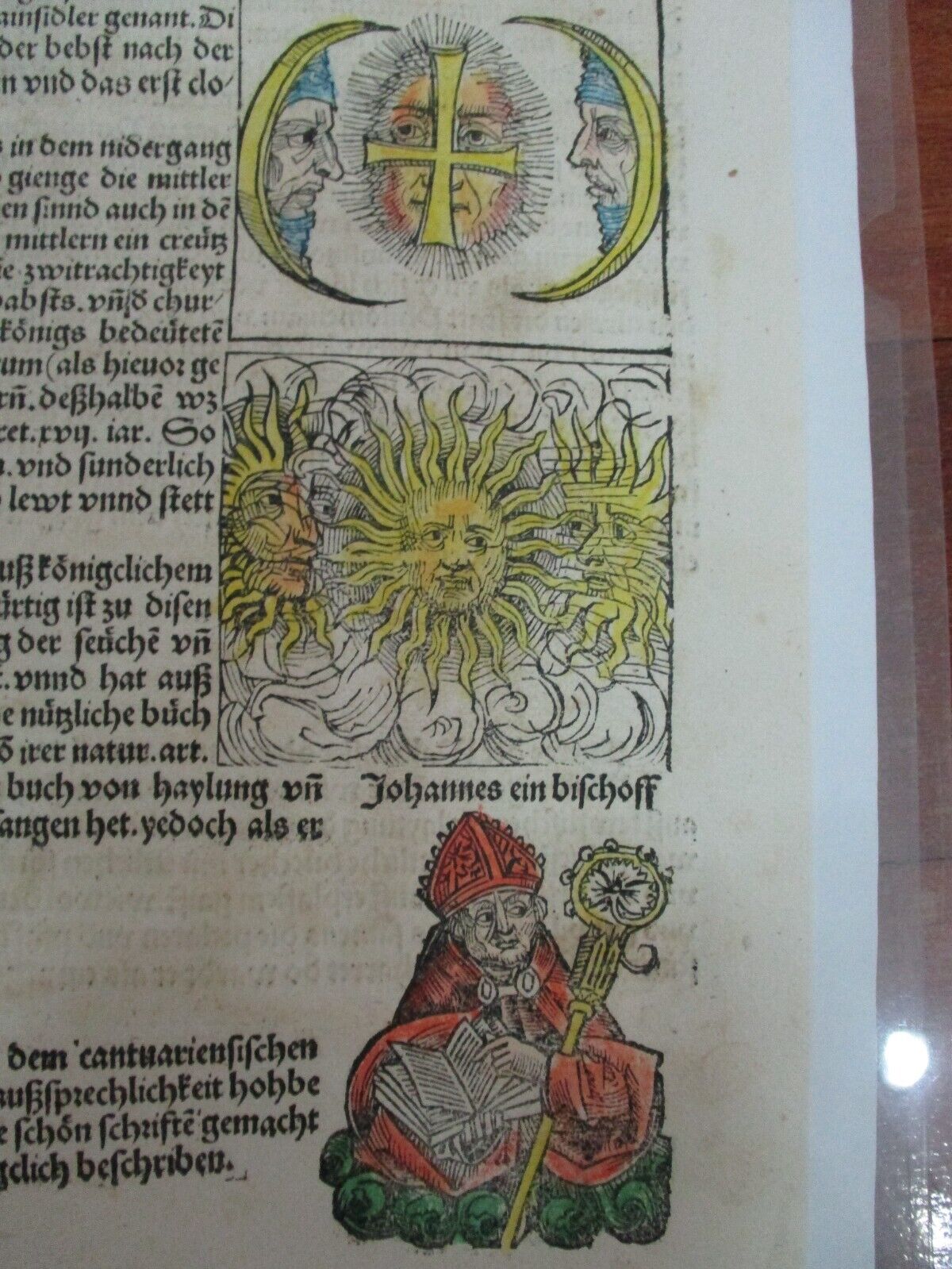

Three Suns, beside one another, were seen in the West at this time, on the Nones of September. The middle one went to rest two hours after the other two had disappeared. In the same manner three moons appeared in the following year. Upon the central one a cross appeared. This phenomenon was interpreted by some as envisioning the dissension of the cardinals in the election of a pope, and of the electors in the election of an emperor. For at this time four popes were elected against Pope Alexander (as previously stated). This was a serious schism, which endured for 17 years.[The Latin text for the concluding phrase of this sentence is:

quod scisma xx. annis. xvii. duravit

, which translates as ‘which schism endured for 20 years 17.’] At this time also occurred such earthquakes, particularly in Syria and Sicily, that land, people and cities were destroyed.

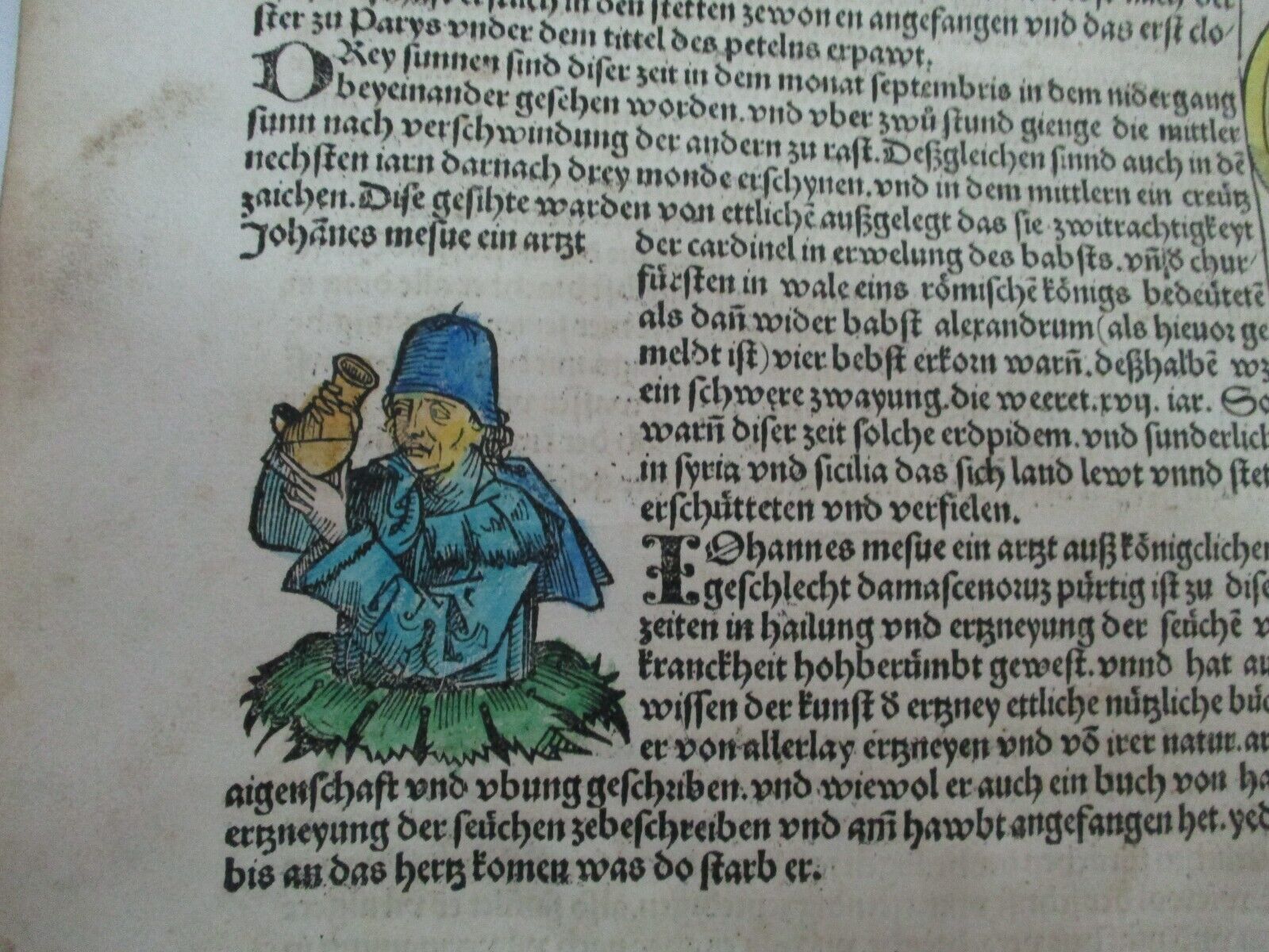

John (Iohannes), son of Mesua, a physician of royal lineage, and a native of Damascus, was highly renowned at this time for his treatment and cure of diseases and plagues. In virtue of his knowledge of the art of medicine, he wrote several useful books on all kinds of medicines and their nature, properties, and application. He also began a book on the treatment and cure of illness, beginning with the head; but he died when he reached the heart.[John, son of Mesua, is supposed to have been a Jacobite Christian from Maradin on the Euphrates, who lived in the 10th century, according to Leo Africanus. As, however, none of his writings have ever been found in their original language and no Arabian bibliographer or biographer knows him, the personality of this author, in the course of time, became more and more improbable. “It is supposed that under the name of Messua is masquerading a Latin author of the twelfth century who hoped thus to obtain more ready recognition of his works.” (Neuburger-Playfair I). According to Sudhoff, the author lived in the beginning of the 13th century in the Upper Italy. At any rate, these works soon gained an authoritative importance as the pharmacological quintessence of Arabistic therapeutics, and the esteem in which they were held is shown by the fact that hey belonged to the first medical books to be printed (Venice, 1471). John’s works consist of three books. The first, , also called , or , deals with the choice of purgatives according to their properties and actions, and with the correction of the same. They are divided into laxative, mild and drastic. The second book, the , or apothecary’s manual (

Antidotarium

), was the most popular compendium of drugs in medieval Europe, and was used everywhere in their preparation. The work stands as the canon of the apothecary’s art in the west, and throughout the Middle Ages was held in highest esteem. The third book, the , is a manual of special therapeutics. It remained incomplete, containing only the diseases of the head and chest, breaking off with the treatment of the heart diseases.]

John, the bishop of Chartres, a confidant of the Blessed Thomas, bishop of Canterbury, and celebrated for his scriptural wisdom, learning and versatility, was held in high esteem and honor at this time. He wrote several beautiful manuscripts. Among others, he very accurately wrote a life of the Blessed Thomas himself.[]

ILLUSTRATIONS

1.

Three Moons, which appeared at the same time, the central one inscribed with a cross. A new woodcut.

2.

John Mesue, a physician, is portrayed as examining a specimen in a bottle.

This one relate the Realization of the St. Agustin Monastery order , Around 1244 AD by pope Inocencius IV

reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_Saint_Augustine

Talt about the life of a famous doctor of the age, famous for his fight against the Black Death.

And the importance about a new bishop named Jahannes in the XIII century

Also talk about some important cosmic event that happened (hard to me to understand, I speak german a little but this is old German) and that they attributed to God.

They talk about the kings on the XIII centuries , in concrete over one named Friederich

Aprox Size:

420x297 mm // 11,693 x 16,535 inches

From

Hartmann Schedel

Original Page